16. Interrupts

- Introduction

- Interrupts registers

- Interrupt Service Routines

- Creating an interrupt switchboard

- Nested interrupt demo

Introduction

Under certain conditions, you can make the CPU drop whatever it’s doing, go run another function instead, and continue with the original process afterwards. This process is known as an interrupt (two ‘r’s, please). The function that handles the interrupt is an interrupt service routine, or just interrupt; triggering one is called raising an interrupt.

Interrupts are often attached to certain hardware events: pressing a key on a PC keyboard, for example, raises one. Another PC example is the VBlank (yes, PCs have them too). The GBA has similar interrupts and others for the HBlank, DMA and more. This last one in particular can be used for a great deal of nifty effects. I’ll give a full list of interrupts shortly.

Interrupts halt the current process, quickly do ‘something’, and pass control back again. Stress the word “quickly”: interrupts are supposed to be short routines.

Interrupts registers

There are three registers specifically for interrupts: REG_IE (0400:0200h), REG_IF (0400:0202h) and REG_IME (0400:0208h). REG_IME is the master interrupt control; unless this is set to ‘1’, interrupts will be ignored completely. To enable a specific interrupt you need to set the appropriate bit in REG_IE. When an interrupt occurs, the corresponding bit in REG_IF will be set. To acknowledge that you’ve handled an interrupt, the bit needs to be cleared again, but the way to do that is a little counter-intuitive to say the least. To acknowledge the interrupt, you actually have to set the bit again. That’s right, you have to write 1 to that bit (which is already 1) in order to clear it.

Apart from setting the bits in REG_IE, you also need to set a bit in other registers that deal with the subject. For example, the HBlank interrupt also requires a bit in REG_DISPSTAT. I think (but please correct me if I’m wrong) that you need both a sender and receiver of interrupts; REG_IE controls the receiver and registers like REG_DISPSTAT control the sender. With that in mind, let’s check out the bit layout for REG_IE and REG_IF.

| F E | D | C | B A 9 8 | 7 | 6 5 4 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| - | C | K | Dma | Com | Tm | Vct | Hbl | Vbl |

| bits | name | define | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Vbl | IRQ_VBLANK | VBlank interrupt. Also requires

REG_DISPSTAT{3}

|

| 1 | Hbl | IRQ_HBLANK | HBlank interrupt. Also requires

REG_DISPSTAT{4} Occurs after the HDraw, so that

things done here take effect in the next line.

|

| 2 | Vct | IRQ_VCOUNT | VCount interrupt. Also requires

REG_DISPSTAT{5}. The high byte of

REG_DISPSTAT gives the VCount at which to raise the

interrupt. Occurs at the beginning of a scanline.

|

| 3-6 | Tm | IRQ_TIMERx | Timer interrupt, 1 bit per timer. Also requires

REG_TMxCNT{6}. The interrupt will be raised

when the timer overflows.

|

| 7 | Com | IRQ_COM | Serial communication interrupt. Apparently, also requires

REG_SCCNT{E}. To be raised when the transfer

is complete. Or so I'm told, I really don't know squat about

serial communication.

|

| 8-B | Dma | IRQ_DMAx | DMA interrupt, 1 bit per channel. Also requires

REG_DMAxCNT{1E}. Interrupt will be raised

when the full transfer is complete.

|

| C | K | IRQ_KEYPAD | Keypad interrupt. Also requires

REG_KEYCNT{E}. Raised when any or all or the keys

specified in REG_KEYCNT are down.

|

| D | C | IRQ_GAMEPAK | Cartridge interrupt. Raised when the cart is removed from the GBA. |

Interrupt Service Routines

You use the interrupt registers described above to indicate which interrupts you want to use. The next step is writing an interrupt service routine. This is just a typeless function (void func(void)); a C-function like many others. Here’s an example of an HBlank interrupt.

void hbl_pal_invert()

{

pal_bg_mem[0] ^= 0x7FFF;

REG_IF = IRQ_HBLANK;

}

The first line inverts the color of the first entry of the palette memory. The second line resets the HBlank bit of REG_IF indicating the interrupt has been dealt with. Since this is an HBlank interrupt, the end-result is that that the color changes every scanline. This shouldn’t be too hard to imagine.

If you simply add this function to an existing program, nothing would change. How come? Well, though you have an isr now, you still need to tell the GBA where to find it. For that, we will need to take a closer look at the interrupt process as a whole.

On acknowledging interrupts correctly

To acknowledge that an interrupt has been dealt with, you have to set the bit of that interrupt in REG_IF, and only that bit. That means that ‘REG_IF = IRQ_x’ is usually the correct course of action, and not ‘REG_IF |= IRQ_x’. The |= version acknowledges all interrupts that have been raised, even if you haven’t dealt with them yet.

Usually, these two result in the same thing, but if multiple interrupts come in at the same time things will go bad. Just pay attention to what you’re doing.

The interrupt process

The complete interrupt process is kind of tricky and part of it is completely beyond your control. What follows now is a list of things that you, the programmer, need to know. For the full story, see GBATEK : irq control.

- Interrupt occurs. Some black magic deep within the deepest dungeons of BIOS happens and the CPU is switched to IRQ mode and ARM state. A number of registers (

r0-r3, r12, lr) are pushed onto the stack. - BIOS loads the address located at

0300:7FFCand branches to that address. - The code pointed to by

0300:7FFCis run. Since we’re in ARM-state now, this must to be ARM code! - After the isr is done, acknowledge that the interrupt has been dealt with by writing to

REG_IF, then return from the isr by issuing abx lrinstruction. - The previously saved registers are popped from stack and program state is restored to normal.

Steps 1, 2 and 5 are done by BIOS; 3 and 4 are yours. Now, in principle all you need to do is place the address of your isr into address 0300:7FFC. To make our job a little easier, we will first create ourselves a function pointer type.

typedef void (*fnptr)(void);

#define REG_ISR_MAIN *(fnptr*)(0x03007FFC)

// Be careful when using it like this, see notes below

void foo()

{

REG_ISR_MAIN= hbl_pal_invert; // tell the GBA where my isr is

REG_DISPSTAT |= VID_HBL_IRQ; // Tell the display to fire HBlank interrupts

REG_IE |= IRQ_HBLANK; // Tell the GBA to catch HBlank interrupts

REG_IME= 1; // Tell the GBA to enable interrupts;

}

Now, this will probably work, but as usual there’s more to the story.

- First, the code that

REG_ISR_MAINjumps to must be ARM code! If you compile with the-mthumbflag, the whole thing comes to a screeching halt. - What happens when you’re interrupted inside an interrupt? Well, that’s not quite possible actually; not unless you do some fancy stuff we’ll get to later. You see,

REG_IMEis not the only thing that allows interrupts, there’s a bit for irqs in the program status register (PSR) as well. When an interrupt is raised, the CPU disables interrupts there until the whole thing is over and done with. hbl_pal_invert()doesn’t check whether it has been activated by an HBlank interrupt. Now, in this case it doesn’t really matter because it’s the only one enabled, but when you use different types of interrupts, sorting them out is essential. That’s why we’ll create an interrupt switchboard in the next section.- Lastly, when you use BIOS calls that require interrupts, you also need to acknowledge them in

REG_IFBIOS(==0300:7FF8). The use is the same asREG_IF.

On section mirroring

GBA’s memory sections are mirrored ever so many bytes. For example IWRAM (0300:0000) is mirrored every 8000h bytes, so that 0300:7FFC is also 03FF:FFFC, or 0400:0000−4. While this is faster, I’m not quite sure if this should be taken advantage of. no$gba v2.2b marks it as an error, even though this was apparently a small oversight and fixed in v2.2c. Nevertheless, consider yourself warned.

Creating an interrupt switchboard

The hbl_pal_invert() function is an example of a single interrupt, but you may have to deal with multiple interrupts. You may also want to be able to use different isr’s depending on circumstances, in which case stuffing it all into one function may not be the best way to go. Instead, we’ll create an interrupt switchboard.

An interrupt switchboard works a little like a telephone switchboard: you have a call (i.e., an interrupt, in REG_IF) coming in, the operator checks if it is an active number (compares it with REG_IE) and if so, connects the call to the right receiver (your isr).

This particular switchboard will come with a number of additional features as well. It will acknowledge the call in both REG_IF and REG_IFBIOS), even when there’s no actual ISR attached to that interrupt. It will also allow nested interrupts, although this requires a little extra work in the ISR itself.

Design and interface considerations

The actual switchboard is only one part of the whole; I also need a couple of structs, variables and functions. The basic items I require are these.

__isr_table[]. An interrupt table. This is a table of function pointers to the different isr’s. Because the interrupts should be prioritized, the table should also indicate which interrupt the pointers belong to. For this, we’ll use anIRQ_RECstruct.irq_init()/irq_set_master(). Set master isr.irq_init()initializes the interrupt table and interrupts themselves as well.irq_enable()/irq_disable(). Functions to enable and disable interrupts. These will take care of bothREG_IEand whatever register the sender bit is on. I’m keeping these bits in an internal table called__irq_senders[]and to be able to use these, the input parameter of these functions need to be the index of the interrupt, not the interrupt flag itself. Which is why I haveII_foocounterparts for theIRQ_fooflags.irq_set()/irq_add()/irq_delete(). Function to add/delete interrupt service routines. The first allows full prioritization of isr’s;irq_add()will replace the current irs for a given interrupt, or add one at the end of the list;irq_delete()will delete one and correct the list for the empty space.

All of these functions do something like this: disable interrupts (REG_IME=0), do their stuff and then re-enable interrupts. It’s a good idea to do this because being interrupted while mucking about with interrupts is not pretty. The functions concerned with service routines will also take a function pointer (the fnptr type), and also return a function pointer indicating the previous isr. This may be useful if you want to try to chain them.

Below you can see the structs, tables, and the implementation of irq_enable() and irq_add(). In both functions, the __irq_senders[] array is used to determine which bit to set in which register to make sure things send interrupt requests. The irq_add() function goes on to finding either the requested interrupt in the current table to replace, or an empty slot to fill. The other routines are similar. If you need to see more, look in tonc_irq.h/.c in libtonc.

//! Interrups Indices

typedef enum eIrqIndex

{

II_VBLANK=0, II_HBLANK, II_VCOUNT, II_TIMER0,

II_TIMER1, II_TIMER2, II_TIMER3, II_SERIAL,

II_DMA0, II_DMA1, II_DMA2, II_DMA3,

II_KEYPAD, II_GAMEPAK,II_MAX

} eIrqIndex;

//! Struct for prioritized irq table

typedef struct IRQ_REC

{

u32 flag; //!< Flag for interrupt in REG_IF, etc

fnptr isr; //!< Pointer to interrupt routine

} IRQ_REC;

// === PROTOTYPES =====================================================

IWRAM_CODE void isr_master_nest();

void irq_init(fnptr isr);

fnptr irq_set_master(fnptr isr);

fnptr irq_add(enum eIrqIndex irq_id, fnptr isr);

fnptr irq_delete(enum eIrqIndex irq_id);

fnptr irq_set(enum eIrqIndex irq_id, fnptr isr, int prio);

void irq_enable(enum eIrqIndex irq_id);

void irq_disable(enum eIrqIndex irq_id);

// IRQ Sender information

typedef struct IRQ_SENDER

{

u16 reg_ofs; //!< sender reg - REG_BASE

u16 flag; //!< irq-bit in sender reg

} ALIGN4 IRQ_SENDER;

// === GLOBALS ========================================================

// One extra entry for guaranteed zero

IRQ_REC __isr_table[II_MAX+1];

static const IRQ_SENDER __irq_senders[] =

{

{ 0x0004, 0x0008 }, // REG_DISPSTAT, DSTAT_VBL_IRQ

{ 0x0004, 0x0010 }, // REG_DISPSTAT, DSTAT_VHB_IRQ

{ 0x0004, 0x0020 }, // REG_DISPSTAT, DSTAT_VCT_IRQ

{ 0x0102, 0x0040 }, // REG_TM0CNT, TM_IRQ

{ 0x0106, 0x0040 }, // REG_TM1CNT, TM_IRQ

{ 0x010A, 0x0040 }, // REG_TM2CNT, TM_IRQ

{ 0x010E, 0x0040 }, // REG_TM3CNT, TM_IRQ

{ 0x0128, 0x4000 }, // REG_SCCNT_L BIT(14) // not sure

{ 0x00BA, 0x4000 }, // REG_DMA0CNT_H, DMA_IRQ>>16

{ 0x00C6, 0x4000 }, // REG_DMA1CNT_H, DMA_IRQ>>16

{ 0x00D2, 0x4000 }, // REG_DMA2CNT_H, DMA_IRQ>>16

{ 0x00DE, 0x4000 }, // REG_DMA3CNT_H, DMA_IRQ>>16

{ 0x0132, 0x4000 }, // REG_KEYCNT, KCNT_IRQ

{ 0x0000, 0x0000 }, // cart: none

};

// === FUNCTIONS ======================================================

//! Enable irq bits in REG_IE and sender bits elsewhere

void irq_enable(enum eIrqIndex irq_id)

{

u16 ime= REG_IME;

REG_IME= 0;

const IRQ_SENDER *sender= &__irq_senders[irq_id];

*(u16*)(REG_BASE+sender->reg_ofs) |= sender->flag;

REG_IE |= BIT(irq_id);

REG_IME= ime;

}

//! Add a specific isr

fnptr irq_add(enum eIrqIndex irq_id, fnptr isr)

{

u16 ime= REG_IME;

REG_IME= 0;

int ii;

u16 irq_flag= BIT(irq_id);

fnptr old_isr;

IRQ_REC *pir= __isr_table;

// Enable irq

const IRQ_SENDER *sender= &__irq_senders[irq_id];

*(u16*)(REG_BASE+sender->reg_ofs) |= sender->flag;

REG_IE |= irq_flag;

// Search for previous occurance, or empty slot

for(ii=0; pir[ii].flag; ii++)

if(pir[ii].flag == irq_flag)

break;

old_isr= pir[ii].isr;

pir[ii].isr= isr;

pir[ii].flag= irq_flag;

REG_IME= ime;

return old_isr;

}

The master interrupt service routine

The main task of the master ISR is to seek out the raised interrupt in ___isr_table, and acknowledge it in both REG_IF and REG_IFBIOS. If there is an irq-specific service routine, it should call it; otherwise, it should just exit to BIOS again. In C, it would look something like this.

// This is mostly what libtonc's isr_master does, but

// you really need asm for the full functionality

IWRAM_CODE void isr_master_c()

{

u32 ie= REG_IE;

u32 ieif= ie & REG_IF;

IRQ_REC *pir;

// (1) Acknowledge IRQ for hardware and BIOS.

REG_IF = ieif;

REG_IFBIOS |= ieif;

// (2) Find raised irq

for(pir= __isr_table; pir->flag!=0; pir++)

if(pir->flag & ieif)

break;

// (3) Just return if irq not found in list or has no isr.

if(pir->flag == 0 || pir->isr == NULL)

return;

// --- If we're here have an interrupt routine ---

// (4a) Disable IME and clear the current IRQ in IE

u32 ime= REG_IME;

REG_IME= 0;

REG_IE &= ~ieif;

// (5a) CPU back to system mode

//> *(--sp_irq)= lr_irq;

//> *(--sp_irq)= spsr

//> cpsr &= ~(CPU_MODE_MASK | CPU_IRQ_OFF);

//> cpsr |= CPU_MODE_SYS;

//> *(--sp_sys) = lr_sys;

pir->isr(); // (6) Run the ISR

REG_IME= 0; // Clear IME again (safety)

// (5b) Back to irq mode

//> lr_sys = *sp_sys++;

//> cpsr &= ~(CPU_MODE_MASK | CPU_IRQ_OFF);

//> cpsr |= CPU_MODE_IRQ | CPU_IRQ_OFF;

//> spsr = *sp_irq++

//> lr_irq = *sp_irq++;

// (4b) Restore original ie and ime

REG_IE= ie;

REG_IME= ime;

}

Most of these points have been discussed already, so I won’t repeat them again. Do note the difference is acknowledging REG_IF and REG_IFBIOS: the former uses a simple assignment and the latter an |=. Steps 4, 5 and 6 only execute if the current IRQ has its own service routine. Steps 4a and 5a work as initialization steps to ensure that the ISR (step 6) can work in CPU mode and that it can’t be interrupted unless it asks for it. Steps 4b and 5b unwind 4a and 5a.

This routine would work fine in C, were it not for items 5a and 5b. These are the code to set/restore the CPU mode to system/irq mode, but the instructions necesasry for that aren’t available in C. Another problem is that the link registers (these are used to hold the return addresses of functions) have to be saved somehow, and these definitely aren’t available in C.

Note: I said registers, plural! Each CPU mode has its own stack and link register, and even though the names are the same (lr and sp), they really aren’t identical. Usually a C routine will save lr on its own, but since you need it twice now it’s very unsafe to leave this up to the compiler. Aside from that, you need to save the saved program status register spsr, which indicates the program status when the interrupt occurred. This is another thing that C can’t really do. As such, assembly is required for the master ISR.

So, assembly it is then. The function below is the assembly equivalent of irs_master_c(). It is almost a line by line translation, although I am making use of a few features of the instruction set the compiler wont’t or can’t. I don’t expect you to really understand everything written here, but with some imagination you should be able to follow most of it. Teaching assembly is way beyond the scope of this chapter, but worth the effort in my view. Tonc’s assembly chapter should give you the necessary information to understand most of it and shows where to go to learn more.

.file "tonc_isr_master.s"

.extern __isr_table;

/*! \fn IWRAM_CODE void isr_master()

\brief Default irq dispatcher (no automatic nesting)

*/

.section .iwram, "ax", %progbits

.arm

.align

.global isr_master

@ --- Register list ---

@ r0 : ®_IE

@ r1 : __isr_table / isr

@ r2 : IF & IE

@ r3 : tmp

@ ip : (IF<<16 | IE)

isr_master:

@ Read IF/IE

mov r0, #0x04000000

ldr ip, [r0, #0x200]!

and r2, ip, ip, lsr #16 @ irq= IE & IF

@ (1) Acknowledge irq in IF and for BIOS

strh r2, [r0, #2]

ldr r3, [r0, #-0x208]

orr r3, r3, r2

str r3, [r0, #-0x208]

@ (2) Search for irq.

ldr r1, =__isr_table

.Lirq_search:

ldr r3, [r1], #8

tst r3, r2

bne .Lpost_search @ Found one, break off search

cmp r3, #0

bne .Lirq_search @ Not here; try next irq

@ (3) Search over : return if no isr, otherwise continue.

.Lpost_search:

ldrne r1, [r1, #-4] @ isr= __isr_table[ii-1].isr

cmpne r1, #0

bxeq lr @ If no isr: quit

@ --- If we're here, we have an isr ---

@ (4a) Disable IME and clear the current IRQ in IE

ldr r3, [r0, #8] @ Read IME

strb r0, [r0, #8] @ Clear IME

bic r2, ip, r2

strh r2, [r0] @ Clear current irq in IE

mrs r2, spsr

stmfd sp!, {r2-r3, ip, lr} @ sprs, IME, (IE,IF), lr_irq

@ (5a) Set mode to sys

mrs r3, cpsr

bic r3, r3, #0xDF

orr r3, r3, #0x1F

msr cpsr, r3

@ (6) Call isr

stmfd sp!, {r0,lr} @ ®_IE, lr_sys

mov lr, pc

bx r1

ldmfd sp!, {r0,lr} @ ®_IE, lr_sys

@ --- Unwind ---

strb r0, [r0, #8] @ Clear IME again (safety)

@ (5b) Reset mode to irq

mrs r3, cpsr

bic r3, r3, #0xDF

orr r3, r3, #0x92

msr cpsr, r3

@ (4b) Restore original spsr, IME, IE, lr_irq

ldmfd sp!, {r2-r3, ip, lr} @ sprs, IME, (IE,IF), lr_irq

msr spsr, r2

strh ip, [r0]

str r3, [r0, #8]

bx lr

Nested irqs are nasty

Making a nested interrupt routine work is not a pleasant exercise when you only partially know what you’re doing. For example, that different CPU modes used different stacks took me a while to figure out, and it took me quite a while to realize that the reason my nested isrs didn’t work was because there are different link registers too.

The isr_master_nest is largely based on libgba’s interrupt dispatcher, but also borrows information from GBATEK and A. Bilyk and DekuTree’s analysis of the whole thing as described in forum:4063. Also invaluable was the home-use debugger version of no$gba, hurray for breakpoints.

If you want to develop your own interrupt routine, these sources will help you immensely and will keep the loss of sanity down to somewhat acceptable levels.

Deprecation notice

I used to have a different master service routine that took care of nesting and prioritizing interrupts automatically. Because it was deemed too complicated, it has been replaced with this one.

Nested interrupts are still possible, but you have to indicate interruptability inside the isr yourself now.

Nested interrupt demo

Today’s demo shows a little bit of everything described above:

- It’ll display a color gradient on the screen through the use of an HBlank interrupt.

- It will allow you to toggle between two different master isrs: The switchboard

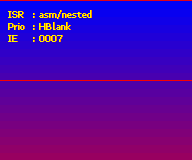

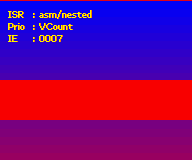

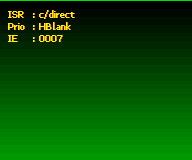

isr_masterwhich routes the program flow to an HBlank isr, and an isr in C that handles the HBlank interrupt directly. For the latter to work, we’ll need to use ARM-compiled code, of course, and I’ll also show you how in a minute. - Finally, having a nested isr switchboard doesn’t mean much unless you can actually see nested interrupts in action. In this case, we’ll use two interrupts: VCount and HBlank. The HBlank isr creates a vertical color gradient. The VCount isr will reset the color and tie up the CPU for several scanlines. If interrupts don’t nest, you’ll see the gradient stop for a while; if they do nest, it’ll continue as normal.

- And just for the hell of it, you can toggle the HBlank and VCount irqs on and off.

The controls are as follows:

| A | Toggles between asm switchboard and C direct isr. |

|---|---|

| B | Toggles HBlank and VCount priorities. |

| L,R | Toggles VCount and HBlank irqs on and off. |

#include <stdio.h>

#include <tonc.h>

IWRAM_CODE void isr_master();

IWRAM_CODE void hbl_grad_direct();

void vct_wait();

void vct_wait_nest();

CSTR strings[]=

{

"asm/nested", "c/direct",

"HBlank", "VCount"

};

// Function pointers to master isrs.

const fnptr master_isrs[2]=

{

(fnptr)isr_master,

(fnptr)hbl_grad_direct

};

// VCount interrupt routines.

const fnptr vct_isrs[2]=

{

vct_wait,

vct_wait_nest

};

// (1) Uses tonc_isr_master.s' isr_master() as a switchboard

void hbl_grad_routed()

{

u32 clr= REG_VCOUNT/8;

pal_bg_mem[0]= RGB15(clr, 0, 31-clr);

}

// (2a) VCT is triggered at line 80; this waits 40 scanlines

void vct_wait()

{

pal_bg_mem[0]= CLR_RED;

while(REG_VCOUNT<120);

}

// (2b) As vct_wait(), but interruptable by HBlank

void vct_wait_nest()

{

pal_bg_mem[0]= CLR_RED;

REG_IE= IRQ_HBLANK; // Allow nested hblanks

REG_IME= 1;

while(REG_VCOUNT<120);

}

int main()

{

u32 bDirect=0, bVctPrio= 0;

tte_init_chr4_b4_default(0, BG_CBB(2)|BG_SBB(28));

tte_set_drawg((fnDrawg)chr4_drawg_b4cts_fast);

tte_init_con();

tte_set_margins(8, 8, 128, 64);

REG_DISPCNT= DCNT_MODE0 | DCNT_BG0;

// (3) Initialize irqs; add HBL and VCT isrs

// and set VCT to trigger at 80

irq_init(master_isrs[0]);

irq_add(II_HBLANK, hbl_grad_routed);

BFN_SET(REG_DISPSTAT, 80, DSTAT_VCT);

irq_add(II_VCOUNT, vct_wait);

irq_add(II_VBLANK, NULL);

while(1)

{

//vid_vsync();

VBlankIntrWait();

key_poll();

// Toggle HBlank irq

if(key_hit(KEY_R))

REG_IE ^= IRQ_HBLANK;

// Toggle Vcount irq

if(key_hit(KEY_L))

REG_IE ^= IRQ_VCOUNT;

// (4) Toggle between

// asm switchblock + hbl_gradient (red, descending)

// or purely hbl_isr_in_c (green, ascending)

if(key_hit(KEY_A))

{

bDirect ^= 1;

irq_set_master(master_isrs[bDirect]);

}

// (5) Switch priorities of HBlank and VCount

if(key_hit(KEY_B))

{

//irq_set(II_VCOUNT, vct_wait, bVctPrio);

bVctPrio ^= 1;

irq_add(II_VCOUNT, vct_isrs[bVctPrio]);

}

tte_printf("#{es;P}IRS#{X:32}: %s\nPrio#{X:32}: %s\nIE#{X:32}: %04X",

strings[bDirect], strings[2+bVctPrio], REG_IE);

}

return 0;

}

The code listing above contains the main demo code, the HBlank, and VCount isrs that will be routed and some sundry items for convenience. The C master isr called hbl_grad_direct() is in another file, which will be discussed later.

First, the contents of the interrupt service routines (points 1 and 2). Both routines are pretty simple: the HBlank routine (hbl_grad_routed()) uses the value of the scanline counter to set a color for the backdrop. At the top, REG_VCOUNT is 0, so the color will be blue; at the bottom, it’ll be 160/8=20, so it’s somewhere between blue and red: purple. Now, you may notice that the first scanline is actually red and not blue: this is because a) the HBlank interrupt occurs after the scanline (which has caused trouble before in the DMA demo) and b) because HBlanks happen during the VBlank as well, so that the color for line 0 is set at REG_VCOUNT=227, which will give a bright red color.

The VCount routines activate at scanline 80. They set the color to red and then waits until scanline 120. The difference between the two is that vct_wait() just waits, but vct_wait_nest() enables the HBlank interrupt. Remember that isr_master disables interrupts before calling an service routine, so the latter Vcount routine should be interrupted by hbl_grad_routed(), but the former would not. As you can see from fig 16.1a and fig 16.1b, this is exactly what happens.

Point 3 is where the interrupts are set up in the first place. The call to irq_init() clears the isr table and sets up the master isr. Its argument can be NULL, in which case the tonc’s default master isr is used. The calls to irq_add() initialize the HBlank and VCount interrupts and their service routines. If you don’t supply a service routine, the switchboard will just acknowledge the interrupt and return. There are times when this is useful, as we’ll see in the next chapter. irq_add() already takes care of both REG_IE and the IRQ bits in REG_DISPSTAT; what it doesn’t do yet is set the VCount at which the interrupt should be triggered, so this is done separately. The order of irq_add() doesn’t really matter, but lower orders are searched first so it makes sense to put more frequent interrupts first.

You can switch between master service routines with irq_set_master(), as is done at point 4. Point 5 chooses between the nested and non-nested VCount routine.

Fig 16.1a: Gradient; nested vct_wait_nested.

|

Fig 16.1b: Gradient; non-nested vct_wait.

|

Fig 16.1c: Gradient; HBlank in master ISR in C. |

This explains most of what the demo can show. For Real Life use, irq_init() and irq_add() are pretty much all you need, but the demo shows some other interesting things as well. Also interesting is that the result is actually a little different for VBA, no$gba and hardware, which brings up another point: interrupts are time-critical routines, and emulating timing is rather tricky. If something works on an emulator but not hardware, interrupts are a good place to start looking.

This almost concludes demo section, except for one thing: the direct HBlank isr in C. But to do that, we need it in ARM code and to make it efficient, it should be in IWRAM as well. And here’s how we do that.

Using ARM + IWRAM code

The master interrupt routines have to be ARM code. As we’ve always compiled to Thumb code, this would be something new. The reason that we’ve always compiled to Thumb code is that the 16bit buses of the normal code sections make ARM-code slow there. However, what we could do is put the ARM code in IWRAM, which has a 32bit bus (and no waitstates) so that it’s actually beneficial to use ARM code there.

Compiling as ARM code is actually quite simple: use -marm instead of -mthumb. The IWRAM part is what causes the most problems. There are GCC extensions that let you specify which section a function should be in. Tonclib has the following macros for them:

#define EWRAM_DATA __attribute__((section(".ewram")))

#define IWRAM_DATA __attribute__((section(".iwram")))

#define EWRAM_BSS __attribute__((section(".sbss")))

#define EWRAM_CODE __attribute__((section(".ewram"), long_call))

#define IWRAM_CODE __attribute__((section(".iwram"), long_call))

// --- Examples of use: ---

// Declarations

extern EWRAM_DATA u8 data[];

IWRAM_CODE void foo();

// Definitions

EWRAM_DATA u8 data[8]= { ... };

IWRAM_CODE void foo()

{

....

}

The EWRAM/IWRAM things should be self-explanatory. The DATA_IN_x things allow global data to be put in those sections. Note that the default section for data is IWRAM anyway, so that may be a little redundant. EWRAM_BSS concerns uninitialized globals. The difference with initialized globals is that they don’t have to take up space in ROM: all you need to know is how much space you need to reserve in RAM for the array.

The function variants also need the long_call attribute. Code branches have a limited range and section branches are usually too far to happen by normal means and this is what makes it work. You can compare them with ‘far’ and ‘near’ that used to be present in PC programming.

It should be noted that these extensions can be somewhat fickle. For one thing, the placement of the attributes in the declarations and definitions seems to matter. I think the examples given work, but if they don’t try to move them around a bit and see if that helps. A bigger problem is that the long_call attribute doesn’t always want to work. Previous experience has led me to believe that the long_call is ignored unless the definition of the function is in another file. If it’s in the same file as the calling function, you’ll get a ‘relocation error’, which basically means that the jump is too far. The upshot of this is that you have to separate your code depending on section as far as functions are concerned. Which works out nicely, as you’ll want to separate ARM code anyway.

So, for ARM/IWRAM code, you need to have a separate file with the routines, use the IWRAM_CODE macro to indicate the section, and use -marm in compilation. It is also a good idea to add -mlong-calls too, in case you ever want to call ROM functions from IWRAM. This option makes every call a long call. Some toolchains (including DKP) have set up their linkscripts so that files with the extension .iwram.c automatically go into IWRAM, so that IWRAM_CODE is only needed for the declaration.

In this case, that’d be the file called isr.iwram.c. This contains a simple master isr in C, and only takes care of the HBlank and acknowledging the interrupts.

#include <tonc.h>

IWRAM_CODE void hbl_grad_direct();

// an interrupt routine purely in C

// (make SURE you compile in ARM mode!!)

void hbl_grad_direct()

{

u32 irqs= REG_IF & REG_IE;

REG_IFBIOS |= irqs;

if(irqs & IRQ_HBLANK)

{

u32 clr= REG_VCOUNT/8;

pal_bg_mem[0]= RGB15(0, clr, 0);

}

REG_IF= irqs;

}

Flags for ARM+IWRAM compilation

Replace the ‘-mthumb’ in your compilation flags by ‘-marm -mlong-calls’. For example:

CBASE := $(INCDIR) -O2 -Wall

# ROM flags

RCFLAGS := $(CBASE) -mthumb-interwork -mthumb

# IWRAM flags

ICFLAGS := $(CBASE) -mthumb-interwork -marm -mlong-calls

For more details, look at the makefile for this project.