9. Regular tiled backgrounds

Tilemap introduction

Tilemaps are the bread and butter for the GBA. Almost every commercial GBA game makes use of tile modes, with the bitmap modes seen only in 3D-like games that use ray-tracing. Everything else uses tiled graphics.

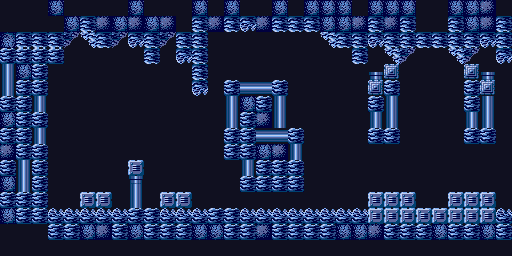

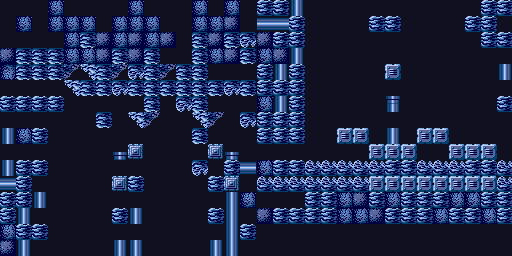

The reason why tilemaps are so popular is that they’re implemented in hardware and require less space than bitmap graphics. Consider fig 9.1a. This is a 512 by 256 image, which even at 8bpp would take up 128 KiB of VRAM, and we simply don’t have that. If you were to make one big bitmap of a normal level in a game, you can easily get up to 1000×1000 pixels, which is just not practical. And then there’s the matter of scrolling through the level, which means updating all pixels each frame. Even when your scrolling code is fully optimized that’d take quite a bit of time.

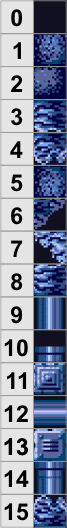

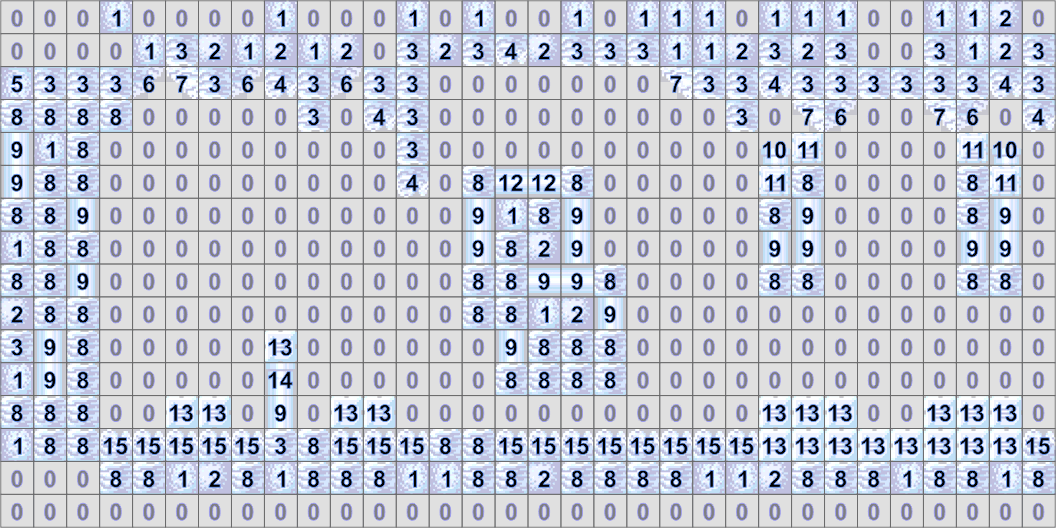

Now, notice that there are many repeated elements in this image. The bitmap seems to be divided into groups of 16×16 pixels. These are the tiles. The list of unique tiles is the tileset, which is given in fig 9.1b. As you can see, there are only 16 unique tiles making up the image. To create the image from these tiles, we need a tilemap. The image is divided into a matrix of tiles. Each element in the matrix has a tile index which indicates which tile should be rendered there; the tilemap can be seen in fig 9.1c.

Suppose both the tileset and map used 8-bit entries, the sizes are 16×(16×16) = 4096 bytes for the tileset and 32×16 = 512 bytes for the tilemap. So that’s 4.5 KiB for the whole scene rather than the 128 KiB we had before; a size reduction of a factor of 28.

Fig 9.1a: image on screen.

Fig 9.1a: image on screen.

| |

| The tile mapping process. Using the tileset of fig 9.1b, and the tile map of fig 9.1c, the end-result is fig 9.1a. | |

Fig 9.1b: the tile set. |

Fig 9.1c: the tile map (with the proper tiles as a backdrop). |

That’s basically how tilemaps work. You don’t define the whole image, but group pixels together into tiles and describe the image in terms of those groups. In the fig 9.1, the tiles were 16×16 pixels, so the tilemap is 256 times smaller than the bitmap. The unique tiles are in the tileset, which can (and usually will) be larger than the tilemap. The size of the tileset can vary: if the bitmap is highly variable, you’ll probably have many unique tiles; if the graphics are nicely aligned to tile boundaries already (as it is here), the tileset will be small. This is why tile-engines often have a distinct look to them.

Tilemaps for the GBA

In the tiled video-modes (0, 1 and 2) you can have up to four backgrounds that display tilemaps. The size of the maps is set by the control registers and can be between 128×128 and 1024×1024 pixels. The size of each tile is always 8×8 pixels, so fig 9.1 isn’t quite the way it’d work on the GBA. Because accessing the tilemaps is done in units of tiles, the map sizes correspond to 16×16 to 128×128 tiles.

Both the tiles and tilemaps are stored in VRAM, which is divided into charblocks and screenblocks. The tileset is stored in the charblocks and the tilemap goes into the screenblocks. In the common vernacular, the word “tile” is used for both the graphical tiles and the entries of the tilemaps. Because this is somewhat confusing, I’ll use the term screen entry (SE for short) as the items in the screenblocks (i.e., the map entries) and restrict tiles to the tileset.

64 KiB of VRAM is set aside for tilemaps (0600:0000h-0600:FFFFh). This is used for both screenblocks and charblocks. You can choose which ones to use freely through the control registers, but be careful that they can overlap (see table 9.1). Each screenblock is 2048 (800h) bytes long, giving 32 screenblocks in total. All but the smallest backgrounds use multiple screenblocks for the full tilemap. Each charblock is 16 KiB (4000h bytes) long, giving four blocks overall.

| Memory | 0600:0000 | 0600:4000 | 0600:8000 | 0600:C000 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| charblock | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||

| screenblock | 0 | … | 7 | 8 | … | 15 | 16 | … | 23 | 24 | … | 31 |

Tiles vs ‘tiles’

Both the entries of the tilemap and the data in the tileset are often referred to as ‘tiles’, which can make conversation confusing. I reserve the term ‘tile’ for the graphics, and ‘screen(block) entry’ or ‘map entry’ for the map’s contents.

Charblocks vs screenblocks

Charblocks and screenblocks use the same addresses in memory. Each charblock overlaps eight screenblocks. When loading data, make sure the tiles themselves don’t overwrite the map, or vice versa.

Size was one of the benefits of using tilemaps, speed was another. The rendering of tilemaps in done in hardware and if you’ve ever played PC games in hardware and software modes, you’ll know that hardware is good. Another nice point is that scrolling is done in hardware too. Instead of redrawing the whole scene, you just have to enter some coordinates in the right registers.

As I said in the overview, there are three stages to setting up a tiled background: control, mapping and image-data. I’ve already covered most of the image-data in the overview, as well as some of the control and mapping parts that are shared by sprites and backgrounds alike; this chapter covers only things specific to backgrounds in general and regular backgrounds in particular. I’m assuming you’ve read the overview.

Essential tilemap steps

- Load the graphics: tiles into charblocks and colors in the background palette.

- Load a map into one or more screenblocks.

- Switch to the right mode in

REG_DISPCNTand activate a background. - Initialize that background’s control register to use the right CBB, SBB and bitdepth.

Background control

Background types

Just like sprites, there are two types of tiled backgrounds: regular and affine; these are also known as text and rotation backgrounds, respectively. The type of the background depends of the video mode (see table 9.2). At their cores, both regular and affine backgrounds work the same way: you have tiles, a tile-map and a few control registers. But that’s where the similarity ends. Affine backgrounds use more and different registers than regular ones, and even the maps are formatted differently. This page only covers the regular backgrounds. I’ll leave the affine ones till after the page on the affine matrix.

| mode | BG0 | BG1 | BG2 | BG3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | reg | reg | reg | reg |

| 1 | reg | reg | aff | - |

| 2 | - | - | aff | aff |

Control registers

All backgrounds have 3 primary control registers. The primary control register is REG_BGxCNT, where x indicates the backgrounds 0 through 3. This register is where you say what the size of the tilemap is, and which charblock and screenblock it uses. The other two are the scrolling registers, REG_BGxHOFS and REG_BGxVOFS.

Each of these is a 16-bit register. REG_BG0CNT can be found at 0400:0008, with the other controls right behind it. The offsets are paired by background, forming coordinate pairs. These start at 0400:0010

| Register | length | address |

|---|---|---|

| REG_BGxCNT | 2 | 0400:0008h + 2·x |

| REG_BGxHOFS | 2 | 0400:0010h + 4·x |

| REG_BGxVOFS | 2 | 0400:0012h + 4·x |

The description of REG_BGxCNT can be found below. Most of it is pretty standard, except for the size: there are actually two lists of possible sizes; one for regular maps and one for affine maps. The both use the same bits you may have to be careful that you’re using the right #defines.

| F E | D | C B A 9 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 4 | 3 2 | 1 0 |

| Sz | Wr | SBB | CM | Mos | - | CBB | Pr |

| bits | name | define | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | Pr | BG_PRIO# | Priority. Determines drawing order of backgrounds. |

| 2-3 | CBB | BG_CBB# | Character Base Block. Sets the charblock that serves as the base for character/tile indexing. Values: 0-3. |

| 6 | Mos | BG_MOSAIC | Mosaic flag. Enables mosaic effect. |

| 7 | CM | BG_4BPP, BG_8BPP | Color Mode. 16 colors (4bpp) if cleared; 256 colors (8bpp) if set. |

| 8-C | SBB | BG_SBB# | Screen Base Block. Sets the screenblock that serves as the base for screen-entry/map indexing. Values: 0-31. |

| D | Wr | BG_WRAP | Affine Wrapping flag. If set, affine background wrap around at their edges. Has no effect on regular backgrounds as they wrap around by default. |

| E-F | Sz | BG_SIZE#, see below | Background Size. Regular and affine backgrounds have different sizes available to them. The sizes, in tiles and in pixels, can be found in table 9.4. |

| Sz-flag | define | (tiles) | (pixels) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | BG_REG_32x32 | 32×32 | 256×256 |

| 01 | BG_REG_64x32 | 64×32 | 512×256 |

| 10 | BG_REG_32x64 | 32×64 | 256×512 |

| 11 | BG_REG_64x64 | 64×64 | 512×512 |

| Sz-flag | define | (tiles) | (pixels) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | BG_AFF_16x16 | 16×16 | 128×128 |

| 01 | BG_AFF_32x32 | 32×32 | 256×256 |

| 10 | BG_AFF_64x64 | 64×64 | 512×512 |

| 11 | BG_AFF_128x128 | 128×128 | 1024×1024 |

Each background has two 16-bit scrolling registers to offset the rendering (REG_BGxHOFS and REG_BGxVOFS). There are a number of interesting points about these. First, because regular backgrounds wrap around, the values are essentially modulo mapsize. This is not really relevant at the moment, but you can use this to your benefit once you get to more advanced tilemaps. Second, these registers are write-only! This is a little annoying, as it means that you can’t update the position by simply doing REG_BG0HOFS++ and the like.

And now the third part, which may be the most important, namely what the values actually do. The simplest way of looking at them is that they give the coordinates of the screen on the map. Read that again, carefully: it’s the position of the screen on the map. It is not the position of the map on the screen, which is how sprites work. The difference is only a minus sign, but even something as small as a sign change can wreak havoc on your calculations.

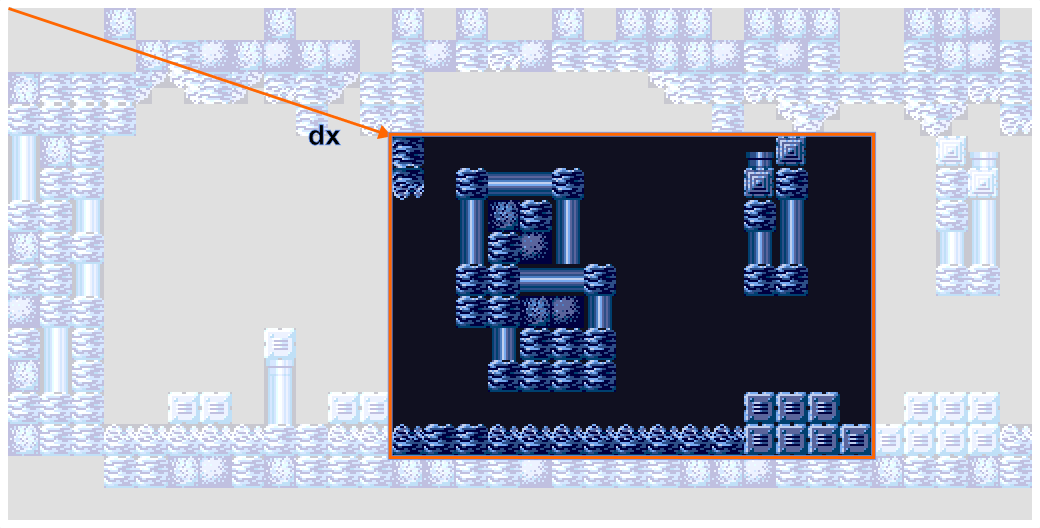

Fig 9.2: Scrolling offset dx sets is the position of the screen on the map. In this case, dx = (192, 64).

So, if you increase the scrolling values, you move the screen to the right, which corresponds to the map moving left on the screen. In mathematical terms, if you have map position p and screen position q, then the following is true:

| (9.1) |

Direction of offset registers

The offset registers REG_BGxHOFS and REG_BGxVOFS indicate which map location is mapped to the top-left of the screen, meaning positive offsets scroll the map left and up. Watch your minus signs.

Offset registers are write only

The offset registers are write-only! That means that direct arithmetic like += will not work.

Useful types and #defines

Tonc’s code has several useful extra types and macros that can make life a little easier.

// === Additional types (tonc_types.h) ================================

//! Screen entry conceptual typedef

typedef u16 SCR_ENTRY;

//! Affine parameter struct for backgrounds, covered later

typedef struct BG_AFFINE

{

s16 pa, pb;

s16 pc, pd;

s32 dx, dy;

} ALIGN4 BG_AFFINE;

//! Regular map offsets

typedef struct BG_POINT

{

s16 x, y;

} ALIGN4 BG_POINT;

//! Screenblock struct

typedef SCR_ENTRY SCREENBLOCK[1024];

// === Memory map #defines (tonc_memmap.h) ============================

//! Screen-entry mapping: se_mem[y][x] is SBB y, entry x

#define se_mem ((SCREENBLOCK*)MEM_VRAM)

//! BG control register array: REG_BGCNT[x] is REG_BGxCNT

#define REG_BGCNT ((vu16*)(REG_BASE+0x0008))

//! BG offset array: REG_BG_OFS[n].x/.y is REG_BGnHOFS / REG_BGnVOFS

#define REG_BG_OFS ((BG_POINT*)(REG_BASE+0x0010))

//! BG affine params array

#define REG_BG_AFFINE ((BG_AFFINE*)(REG_BASE+0x0000))

Strictly speaking, making a SCREEN_ENTRY typedef is not necessary, but makes its use clearer. se_mem works much like tile_mem: it maps out VRAM into screenblocks screen-entries, making finding a specific entry easier. The other typedefs are used to map out arrays for the background registers. For example, REG_BGCNT is an array that maps out all REG_BGxCNT registers. REG_BGCNT[0] is REG_BG0CNT, etc. The BG_POINT and BG_AFFINE types are used in similar fashions. Note that REG_BG_OFS still covers the same registers as REG_BGxHOFS and REG_BGxVOFS do, and the write-only-ness of them has not magically disappeared. The same goes for REG_BG_AFFINE, but that discussion will be saved for another time.

In theory, it is also useful create a sort of background API, with a struct with the temporaries for map positioning and functions for initializing and updating the registers and maps. However, most of tonc’s demos are not complex enough to warrant these things. With the types above, manipulating the necessary items is already simplified enough for now.

Regular background tile-maps

The screenblocks form a matrix of screen entries that describe the full image on the screen. In the example of fig 9.1, the tilemap entries just contained the tile index. The GBA screen entries bahave a little differently.

For regular tilemaps, each screen entry is 16-bits long. Besides the tile index, it contains flipping flags and a palette bank index for 4bpp / 16-color tiles. The exact layout can be found in “Screen entry format” below. The affine screen entries are only 8 bits wide and just contain an 8-bit tile index.

| F E D C | B | A | 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 |

| PB | VF | HF | TID |

| bits | name | define | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | TID | SE_ID# | Tile-index of the SE. |

| A-B | HF, VF | SE_HFLIP, SE_VFLIP. SE_FLIP# | Horizontal/vertical flipping flags. |

| C-F | PB | SE_PALBANK# | Palette bank to use when in 16-color mode. Has no effect

for 256-color bgs (REG_BGxCNT{6} is set).

|

Map layout

VRAM contains 32 screenblocks to store the tilemaps in. Each screenblock is 800h bytes long, so you can fit 32×32 screen entries into it, which equals one 256×256 pixel map. The bigger maps simply use more than one screenblock. The screenblock index set in REG_BGxCNT is the screen base block which indicates the start of the tilemap.

Now, suppose you have a tilemap that’s tw×th tiles/SEs in size. You might expect that the screen entry at tile-coordinates (tx, ty) could be found at SE-number n = tx+ty·tw, because that’s how matrices always work, right? Well, you’d be wrong. At least, you’d be partially wrong.

Within each screenblock the equation works, but the bigger backgrounds don’t simply use multiple screenblocks, they’re actually accessed as four separate maps. How this works can be seen in table 9.5: each numbered block is a contingent block in memory. This means that to get the SE-index you have to find out which screenblock you are in and then find the SE-number inside that screenblock.

| 32×32 | 64×32 | 32×64 | 64×64 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

This kind of nesting problem isn’t as hard as it looks. We know how many tiles fit in a screenblock, so to get the SBB-coordinates, all we have to do divide the tile-coords by the SBB width and height: sbx=tx/32 and sby=ty/32. The SBB-number can then be found with the standard matrix→array formula. To find the in-SBB SE-number, we have to use tx%32 and ty%32 to find the in-SBB coordinates, and then again the conversion from 2D coords to a single element. This is to be offset by the SBB-number tiles the size of an SBB to find the final number. The final form would be:

//! Get the screen entry index for a tile-coord pair

// And yes, the div and mods will be converted by the compiler

uint se_index(uint tx, uint ty, uint pitch)

{

uint sbb= (ty/32)*(pitch/32) + (tx/32);

return sbb*1024 + (ty%32)*32 + tx%32;

}

The general formula is left as an exercise for the reader – one that is well worth the effort, in my view. This kind of process crops up in a number of places, like getting the offset for bitmap coordinates in tiles, and tile coords in 1D object mapping.

If all those operations make you queasy, there’s also a faster version specifically for a 2×2 arrangement. It starts with calculating the number as if it’s a 32×32t map. This will be incorrect for a 64t wide map, which we can correct for by adding 0x0400−0x20 (i.e., tiles/block − tiles per row). We need another full block correction is the size is 64×64t.

//! Get the screen entry index for a tile-coord pair.

/*! This is the fast (and possibly unsafe) way.

* \param bgcnt Control flags for this background (to find its size)

*/

uint se_index_fast(uint tx, uint ty, u16 bgcnt)

{

uint n= tx + ty*32;

if(tx >= 32)

n += 0x03E0;

if(ty >= 32 && (bgcnt&BG_REG_64x64)==BG_REG_64x64)

n += 0x0400;

return n;

}

I would like to remind you that n here is the SE-number, not the address. Since the size of a regular SE is 2 bytes, you need to multiply n by 2 for the address. (Unless, of course, you have a pointer/array of u16s, in which case n will work fine.) Also, this works for regular backgrounds only; affine backgrounds use a linear map structure, which makes this extra work unnecessary there. By the way, both the screen-entry and map layouts are different for affine backgrounds. For their formats, see the map format section of the affine background page.

Background tile subtleties

There are two additional things you need to be aware of when using tiles for tile-maps. The first concerns tile-numbering. For sprites, numbering went according to 4-bit tiles (s-tiles); for 8-bit tiles (d-tiles) you’d have use multiples of 2 (a bit like u16 addresses are always multiples of 2 in memory). In tile-maps, however, d-tiles are numbered by the d-tile. To put it in other words, for sprites, using index id indicates the same tile for both 4 and 8-bit tiles, namely the one that starts at id·20h. For tile-maps, however, it starts at id·20h for 4-bit tiles, but at id·40h for 8-bit tiles.

| memory offset | 000h | 020h | 040h | 060h | 080h | 100h | ... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4bpp tile | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ... |

| 8bpp tile | 0 | 1 | 2 | ... | |||

The second concerns, well, also tile-numbering, but more how many tiles you can use. Each map entry for regular backgrounds has 10 bits for a tile index, so you can use up to 1024 tiles. However, a quick calculation shows that a charblock contains 4000h/20h= 512 s-tiles, or 4000h/40h= 256 d-tiles. So what’s the deal here? Well, the charblock index you set in REG_BGxCNT is actually only the block where tile-counting starts: its character base block. You can use the ones after it as well. Cool, huh? But wait, if you can access subsequent charblocks as well; does this mean that, if you set the base charblock to 3, you can use the sprite blocks (which are basically blocks 4 and 5) as well?

The answer is: yes. And NO!

Emulators from the early 2000s allow you to do this. However, a real GBA doesn’t. It does output something, though: the screen-entry will be used as tile-data itself, but in a manner that simply defies explanation. Trust me on this one, okay? Of the current tonc demos, this is one of the times that VBA gets it wrong.

Available tiles

For both 4bpp and 8bpp regular bgs, you can access 1024 tiles. The only caveat here is that you cannot access the tiles in the object charblocks even if the index would call for it.

Another thing you may be wondering is if you can use a particular screenblock that is within a currently used charblock. For example, is it allowed to have a background use charblock 0 and screenblock 1. Again, yes you can do this. This can be useful since you’re not likely to fill an entire charblock, so using its later screenblocks for your map data is a good idea. (A sign of True Hackerdom would be if you manage to use the same data for both tiles and SEs and still get a meaningful image (this last part is important). If you have done this, please let me know.)

Tilemap data conversion via CLI

A converter that can tile images (for objects), can also create a tileset for tilemaps, although there will likely be many redundant tiles. A few converters can also reduce the tileset to only the unique tiles, and provide the tilemap that goes with it. The Brinstar bitmap from fig 9.1 is a 512×256 image, which could be tiled to a 64×32 map with a 4bpp tileset reduced for uniqueness in tiles, including palette info and mirroring.

# gfx2gba

# (C array; u8 foo_Tiles[], u16 foo_Map[],

# u16 master_Palette[]; foo.raw.c, foo.map.c, master.pal.c)

gfx2gba -fsrc -c16 -t8 -m foo.bmp

# grit

# (C array; u32 fooTiles[], u16 fooMap[], u16 fooPal[]; foo.c, foo.h)

grit foo.bmp -gB4 -mRtpf

Two notes on gfx2gba: First, it merges the palette to a single 16-color array, rearranging it in the process. Second, while it lists metamapping options in the readme, it actually doesn’t give a metamap and meta-tileset, it just formats the map into different blocks.

Tilemap demos

There are four demos in this chapter. The first one is brin_demo, which is very, very short and shows the basic steps of tile loading and scrolling. The next ones are called sbb_reg and cbb_demo, which are tech demos, illustrating the layout of multiple screenblocks and how tile indexing is done on 4bpp and 8bpp backgrounds. In both these cases, the map data is created manually because it’s more convenient to do so here, but using map-data created by map editors really isn’t that different.

Essential tilemap steps: brin_demo

As I’ve been using a 512×256 part of Brinstar throughout this chapter, I thought I might as well use it for a demo.

There are a few map editors out there that you can use. Two good ones are Nessie’s MapEd or Mappy, both of which have a number of interesting features. I have my own map editor, mirach, but it’s just a very basic thing. Some tutorials may point you to GBAMapEditor. Do not use this editor as it’s pretty buggy, leaving out half of the tilemaps sometimes. Tilemaps can be troublesome enough for beginners without having to worry about whether the map data is faulty.

In this cause, however, I haven’t used any editor at all. Some of the graphics converters can convert to a tileset+tilemap – it’s not the standard method, but for small maps it may well be easier. In this case I’ve used Usenti to do it, but grit and gfx2gba work just as well. Note that because the map here is 64×32 tiles, which requires splitting into screenblocks. In Usenti this is called the ‘sbb’ layout, in grit it’s ‘-mLs’ and for gfx2gba you’d use ‘-mm 32’ … I think. In any case, after a conversion you’d have a palette, a tileset and a tilemap.

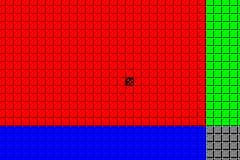

Fig 9.3a: brin_demo palette. |

|

Fig 9.3b: brin_demo tileset. |

In fig 9.3 you can see the full palette, the tileset and part of the map. Note that the tileset of fig 9.3b is not the same as that of fig 9.1b because the former uses 8×8 tiles while the latter used 16×16 tiles. Note also that the screen entries you see here are either 0 (i.e., the empty tile) or of the form 0x3xxx. The high nybble indicates the palette bank, in this case three. If you’d look to the palette (fig 9.3a) you’d see that this gives bluish colors.

Now on to using these data. Remember the essential steps here:

- Load the graphics: tiles into charblocks and colors in the background palette.

- Load a map into one or more screenblocks.

- Switch to the right mode in

REG_DISPCNTand activate a background. - Initialize that background’s control register to use the right CBB, SBB and bitdepth.

If you do it correctly, you should have something showing on screen. If not, go to the tile/map/memory viewers of your emulator; they’ll usually give you a good idea where the problem is. A common one is having a mismatch between the CBB and SBB in REG_BGxCNT and where you put the data, which most likely would leave you with an empty map or empty tileset.

The full code of brin_demo is given below. The three calls to memcpy() load up the palette, tileset and tilemap. For some reason, probably related to where the NES and 8-bit Game Boy put screenblocks in video memory, it’s become conventional to place the maps in the last screenblocks on GBA as well. In this case, that’s 30 rather than 31 because we need two blocks for a 64×32t map. For the scrolling part, I’m using two variables to store and update the positions because the scrolling registers are write-only. I’m starting at (192, 64) here because that’s what I used for the scrolling picture of fig 9.2 earlier.

#include <string.h>

#include "toolbox.h"

#include "input.h"

#include "brin.h"

int main()

{

// Load palette

memcpy(pal_bg_mem, brinPal, brinPalLen);

// Load tiles into CBB 0

memcpy(&tile_mem[0][0], brinTiles, brinTilesLen);

// Load map into SBB 30

memcpy(&se_mem[30][0], brinMap, brinMapLen);

// set up BG0 for a 4bpp 64x32t map, using

// using charblock 0 and screenblock 31

REG_BG0CNT= BG_CBB(0) | BG_SBB(30) | BG_4BPP | BG_REG_64x32;

REG_DISPCNT= DCNT_MODE0 | DCNT_BG0;

// Scroll around some

int x= 192, y= 64;

while(1)

{

vid_vsync();

key_poll();

x += key_tri_horz();

y += key_tri_vert();

REG_BG0HOFS= x;

REG_BG0VOFS= y;

}

return 0;

}

Fig 9.4a: brin_demo at dx=(192, 64). |

Fig 9.4b: brin_demo at dx=(0, 0). |

Interlude: Fast-copying of non sbb-prepared maps

This is not exactly required knowledge, but should make for an interesting read. In this demo I use a multi-sbb map that was already prepared for that. The converter made sure that the left block of the map came before the right block. If this weren’t the case then you couldn’t load the whole map in one go because the second row of the left block would use the first row of the right block and so on (see fig 9.5).

Fig 9.5 brin_demo without blocking out into SBB's first.

There are few simple and slow ways and one simple and fast way of copying a non sbb-prepared map to a multiple screenblocks. The slow way would be to perform a double loop to go row by row of each screenblock. The fast way is through struct-copies and pointer arithmetic, like this:

typedef struct { u32 data[8]; } BLOCK;

int iy;

BLOCK *src= (BLOCK*)brinMap;

BLOCK *dst0= (BLOCK*)se_mem[30];

BLOCK *dst1= (BLOCK*)se_mem[31];

for(iy=0; iy<32; iy++)

{

// Copy row iy of the left half

*dst0++= *src++; *dst0++= *src++;

// Copy row iy of the right half

*dst1++= *src++; *dst1++= *src++;

}

A BLOCK struct-copy takes care of half a row, so two takes care of a whole screenblock row (yes, you could define BLOCK as a 16-word struct, but that wouldn’t work out anymore. Trust me). At that point, the src pointer has arrived at the right half of the map, so we copy the next row into the right-hand side destination, dst1. When done with that, src points to the second row of the left side. Now do this for all 32 lines. Huzzah for struct-copies, and pointers!

A screenblock demo

The second demo, sbb_reg, uses a 64×64t background to indicate how multiple screenblocks are used for bigger maps in more detail. While the brin_demo used a multi-sbb map as well, it wasn’t easy to see what’s what because the map was irregular; this demo uses a very simple tileset so you can clearly see the screenblock boundaries. It’ll also show how you can use the REG_BG_OFS registers for scrolling rather than REG_BGxHOFS and REG_BGxVOFS.

#include "toolbox.h"

#include "input.h"

#define CBB_0 0

#define SBB_0 28

#define CROSS_TX 15

#define CROSS_TY 10

BG_POINT bg0_pt= { 0, 0 };

SCR_ENTRY *bg0_map= se_mem[SBB_0];

uint se_index(uint tx, uint ty, uint pitch)

{

uint sbb= ((tx>>5)+(ty>>5)*(pitch>>5));

return sbb*1024 + ((tx&31)+(ty&31)*32);

}

void init_map()

{

int ii, jj;

// initialize a background

REG_BG0CNT= BG_CBB(CBB_0) | BG_SBB(SBB_0) | BG_REG_64x64;

REG_BG0HOFS= 0;

REG_BG0VOFS= 0;

// (1) create the tiles: basic tile and a cross

const TILE tiles[2]=

{

{{0x11111111, 0x01111111, 0x01111111, 0x01111111,

0x01111111, 0x01111111, 0x01111111, 0x00000001}},

{{0x00000000, 0x00100100, 0x01100110, 0x00011000,

0x00011000, 0x01100110, 0x00100100, 0x00000000}},

};

tile_mem[CBB_0][0]= tiles[0];

tile_mem[CBB_0][1]= tiles[1];

// (2) create a palette

pal_bg_bank[0][1]= RGB15(31, 0, 0);

pal_bg_bank[1][1]= RGB15( 0, 31, 0);

pal_bg_bank[2][1]= RGB15( 0, 0, 31);

pal_bg_bank[3][1]= RGB15(16, 16, 16);

// (3) Create a map: four contingent blocks of

// 0x0000, 0x1000, 0x2000, 0x3000.

SCR_ENTRY *pse= bg0_map;

for(ii=0; ii<4; ii++)

for(jj=0; jj<32*32; jj++)

*pse++= SE_PALBANK(ii) | 0;

}

int main()

{

init_map();

REG_DISPCNT= DCNT_MODE0 | DCNT_BG0 | DCNT_OBJ;

u32 tx, ty, se_curr, se_prev= CROSS_TY*32+CROSS_TX;

bg0_map[se_prev]++; // initial position of cross

while(1)

{

vid_vsync();

key_poll();

// (4) Moving around

bg0_pt.x += key_tri_horz();

bg0_pt.y += key_tri_vert();

// (5) Testing se_index

// If all goes well the cross should be around the center of

// the screen at all times.

tx= ((bg0_pt.x>>3)+CROSS_TX) & 0x3F;

ty= ((bg0_pt.y>>3)+CROSS_TY) & 0x3F;

se_curr= se_index(tx, ty, 64);

if(se_curr != se_prev)

{

bg0_map[se_prev]--;

bg0_map[se_curr]++;

se_prev= se_curr;

}

REG_BG_OFS[0]= bg0_pt; // write new position

}

return 0;

}

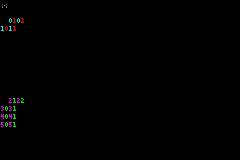

Fig 9.6: sbb_reg. Compare table 9.5, 64×64t background. Note the little cross in the top left corner.

The init_map() contains all of the initialization steps: setting up the registers, tiles, palettes and maps. Unlike the previous demo, the tiles, palette and the map are all created manually because it’s just easier in this case. At point (1), I define two tiles. The first one looks a little like a pane and the second one is a rudimentary cross. You can see them clearly in the screenshot (fig 9.4). The pane-like tile is loaded into tile 0, and is therefore the ‘default’ tile for the map.

The palette is set at point (2). The colors are the same as in table 9.5: red, green, blue and grey. Take note of which palette entries I’m using: the colors are in different palette banks so that I can use palette swapping when I fill the map. Speaking of which …

Loading the map itself (point (3)) happens through a double loop. The outer loop sets the palette-bank for the screen entries. The inner loop fills 1024 SEs with palette-swapped tile-0’s. Now, if big maps used a flat layout, the result would be a big map in four colored bands. However, what actually happens is that you see blocks, not bands, proving that indeed regular maps are split into screenblocks just like table 9.5 said. Yes, it’s annoying, but that’s just the way it is.

That was creating the map, now we turn to the main loop in main(). The keys (point (4)) let you scroll around the map. The RIGHT button is tied to a positive change in x, but the map itself actually scrolls to the left! When I say it like that it may seem counter-intuitive, but if you look at the demo you see that it actually makes sense. Think of it from a hypothetical player sprite point of view. As the sprite moves through the world, you need to update the background to keep the sprite from going off-screen. To do that, the background’s movement should be the opposite of the sprite’s movement. For example, if the sprite moves to the right, you have to move the background to the left to compensate.

Finally, there’s one more thing to discuss: the cross that appears centered on the map. To do this as you scroll along, I keep track of the screen-entry at the center of the screen via a number of variables and the se_index() function. Variables tx and ty are the tile coordinates of the center of the screen, found by shifting and masking the background pixel coordinates. Feeding these to se_index() gives me the screen-entry offset from the screen base block. If this is different than the previous offset, I repaint the former offset as a pane, and update the new offset to the cross. That way, the cross seems to move over the map; much like a sprite would. This was actually designed as a test for se_index(); if the function was flawed, the cross would just disappear at some point. But it doesn’t. Yay me ^_^

The charblock demo

The third demo, cbb_demo, covers some of the details of charblocks and the differences in 4bpp and 8bpp tiles. The backgrounds in question are BG 0 and BG 1. Both will be 32×32t backgrounds, but BG 0 will use 4bpp tiles and CBB 0 and BG 2 uses 8bpp tiles and CBB 2. The exact locations and contents of the screenblocks are not important; what is important is to load the tiles to the starts of all 6 charblocks and see what happens.

#include <toolbox.h>

#include "cbb_ids.h"

#define CBB_4 0

#define SBB_4 2

#define CBB_8 2

#define SBB_8 4

void load_tiles()

{

int ii;

TILE *tl= (TILE*)ids4Tiles;

TILE8 *tl8= (TILE8*)ids8Tiles;

// Loading tiles. don't get freaked out on how it looks

// 4-bit tiles to blocks 0 and 1

tile_mem[0][1]= tl[1]; tile_mem[0][2]= tl[2];

tile_mem[1][0]= tl[3]; tile_mem[1][1]= tl[4];

// and the 8-bit tiles to blocks 2 though 5

tile8_mem[2][1]= tl8[1]; tile8_mem[2][2]= tl8[2];

tile8_mem[3][0]= tl8[3]; tile8_mem[3][1]= tl8[4];

tile8_mem[4][0]= tl8[5]; tile8_mem[4][1]= tl8[6];

tile8_mem[5][0]= tl8[7]; tile8_mem[5][1]= tl8[8];

// And let's not forget the palette (yes, obj pal too)

u16 *src= (u16*)ids4Pal;

for(ii=0; ii<16; ii++)

pal_bg_mem[ii]= pal_obj_mem[ii]= *src++;

}

void init_maps()

{

// se4 and se8 map coords: (0,2) and (0,8)

SB_ENTRY *se4= &se_mem[SBB_4][2*32], *se8= &se_mem[SBB_8][8*32];

// show first tiles of char-blocks available to bg0

// tiles 1, 2 of char-block CBB_4

se4[0x01]= 0x0001; se4[0x02]= 0x0002;

// tiles 0, 1 of char-block CBB_4+1

se4[0x20]= 0x0200; se4[0x21]= 0x0201;

// show first tiles of char-blocks available to bg1

// tiles 1, 2 of char-block CBB_8 (== 2)

se8[0x01]= 0x0001; se8[0x02]= 0x0002;

// tiles 1, 2 of char-block CBB_8+1

se8[0x20]= 0x0100; se8[0x21]= 0x0101;

// tiles 1, 2 of char-block CBB_8+2 (== CBB_OBJ_LO)

se8[0x40]= 0x0200; se8[0x41]= 0x0201;

// tiles 1, 2 of char-block CBB_8+3 (== CBB_OBJ_HI)

se8[0x60]= 0x0300; se8[0x61]= 0x0301;

}

int main()

{

load_tiles();

init_maps();

// init backgrounds

REG_BG0CNT= BG_CBB(CBB_4) | BG_SBB(SBB_4) | BG_4BPP;

REG_BG1CNT= BG_CBB(CBB_8) | BG_SBB(SBB_8) | BG_8BPP;

// enable backgrounds

REG_DISPCNT= DCNT_MODE0 | DCNT_BG0 | DCNT_BG1 | DCNT_OBJ;

while(1);

return 0;

}

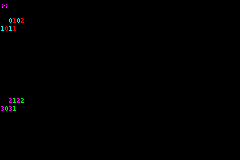

The tilesets can be found in cbb_ids.c. Each tile contains two numbers: one for the charblock I’m putting it and one for the tile-index in that block. For example, the tile that I want in charblock 0 at tile 1 shows ‘01’, CBB 1 tile 0 shows ‘10’, CBB 1, tile 1 has ‘11’, etc. I have twelve tiles in total, 4 s-tiles to be used for BG 0 and 8 d-tiles for BG 1.

Now, I have six pairs of tiles and I intend to place them in the first tiles of each of the 6 charblock (except for CBBs 0 and 2, where tile 0 would be used as default tiles for the background, which I want to keep empty). Yes six, I’m loading into the sprite charblocks as well. I could do this by hand, calculating all the addresses manually (0600:0020 for CBB 0, tile 1, etc) and hope I don’t make a mistake and can remember what I’m doing when revisiting the demo later, or I can just use my tile_mem and tile8_mem memory map matrices and get the addresses quickly and without any hassle. Even better, C allows struct assignments so I can load the individual tiles with a simple assignment! That is exactly what I’m doing in load_tiles(). The source tiles are cast to TILE and TILE8 arrays for 4bpp and 8bpp tiles respectively. After that, loading the tiles is very simple indeed.

The maps themselves are created in init_maps(). The only thing I’m interested in for this demo is to show how and which charblocks are used, so the particulars of the map aren’t that important. The only thing I want them to do is to be able to show the tiles that I loaded in load_tiles(). The two pointers I create here, se4 and se8, point to screen-entries in the screenblocks used for BG 0 and BG 1, respectively. BG 0’s map, containing s-tiles, uses 1 and 512 offsets; BG 1’s entries, 8bpp tiles, carries 1 and 256 offsets. If what I said before about tile-index for different bitdepths is true, then you should see the contents of all the loaded tiles. And looking at the result of the demo (fig 9.7), it looks as if I did my math correctly: background tile-indices follow the bg’s assigned bitdepth, in contrast to sprites which always counts in 32 byte offsets.

There is, however, one point of concern: on hardware, you won’t see the tiles that are actually in object VRAM (blocks 4 and 5). While you might expect to be able to use the sprite blocks for backgrounds due to the addresses, the actual wiring in the GBA seems to forbid it. This is why you should test on hardware is important: emulators aren’t always perfect. But if hardware testing is not available to you, test on multiple emulators; if you see different behaviour, be wary of the code that produced it.

Fig 9.7a: cbb_demo on obsolete emulators (such as VBA and Boycott Adv). |

Fig 9.7b: cbb_demo on hardware. Spot the differences! |

Bonus demo: the ‘text’ in text bg and introducing libtonc

Woo, bonus demo! This example will serve a number of purposes. The first is to introduce libtonc, a library of code to make life on the GBA a bit easier. In past demos, I’ve been using toolbox.h/c to store useful macros and functions. This is alright for very small projects, but as code gets added, it becomes very hard to maintain everything. It’s better to store common functionality in libraries that can be shared among projects.

The second reason is to show how you can output text, which is obviously an important ability to have. Tonclib has an extensive list of options for text rendering – too much to explain here – but its interface is pretty easy. For details, visit the Tonc Text Engine chapter.

Anyway, here’s the example.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <tonc.h>

int main()

{

REG_DISPCNT= DCNT_MODE0 | DCNT_BG0;

// Init BG 0 for text on screen entries.

tte_init_se_default(0, BG_CBB(0)|BG_SBB(31));

tte_write("#{P:72,64}"); // Goto (72, 64).

tte_write("Hello World!"); // Print "Hello world!"

while(1);

return 0;

}

Fig 9.8a: hello demo. |

Fig 9.8b: tileset of the hello demo. |

Yes, it is indeed a “hello world” demo, the starting point of nearly every introductory C/C++ tutorial. However, those are usually for meant for PC platforms, which have native console functionality like printf() or cout. These do not exist for the GBA. (Or “didn’t”, I should say; there are ways to make use of them nowadays. See tte:conio for details.)

Tonc’s support for text goes through tte_ functions. In this case, tte_init_se_default() sets up background 0 for tile-mapped text. It also loads the default 8×8 font into charblock 0 (see fig 9.8b). After that, you can write to text with tte_write. The sequence #{P:x,y} is the formatting command that TTE uses to position the cursor. There are a number of these, some of which you’ll also see in later chapters.

From this point on, I’ll make liberal use of libtonc’s text capabilities in examples for displaying values and the like. This will mostly happen without explanation, because that won’t be part of the demo. Again, to see the internals, go to the TTE chapter.

Creating and using code libraries

Using the functions themselves is pretty simple, but they are spread out over multiple files and reference even more. This makes it a hassle to find which files you need to add to the list of sources to compile a project. You could add everything, of course, but that’s not a pleasant prospect either. The best solution is to pre-compile the utility code into a library.

Libraries are essentially clusters of object files. Instead of linking the objects into an executable directly, you archive them with arm-none-eabi-ar. The command is similar to the link step as well. Here is how you can create the library libfoo.a from objects foo.o, bar.o and baz.o.

# archive rule

libfoo : foo.o bar.o baz.o

arm-none-eabi-ar -crs libfoo.a foo.o bar.o baz.o

# shorthand rule: $(AR) rcs $@ $^

The three flags stand for create archive, replace member and create symbol table, respectively. For more on these and other archiving flags, I will refer you to the manual, which is part of the binutils toolset. The flags are followed by the library name, which is followed by all the objects (the ‘members’ you want to archive).

To use the library, you have to link it to the executable. There are two linker flags of interest here: -L and -l. Upper- and lowercase ‘L’. The former, -L adds a library path. The lowercase version, -l, adds the actual library, but there is a twist here: only need the root-name of the library. For example, to link the library libfoo.a, use -lfoo. The prefix lib and extension .a are assumed by the linker.

# using libfoo (assume it's in ../lib)

$(PROJ).elf : $(OBJS)

$(LD) $^ $(LDFLAGS) -L../lib -lfoo -o $@

Of course, these archives can get pretty big if you dump a lot of stuff in there. You might wonder if all of it is linked when you add a library to your project. The answer is no, it is not. The linker is smart enough to use only the files which functions you’re actually referencing. In the case of this demo, for example, I’m using various text functions, but none of the affine functions or tables, so those are excluded. Note that the exclusion goes by file, not by function. If you only have one file in the library (or #included everything, which amounts to the same thing), everything will be linked.

I intend to use libtonc in a number of later demos. In particular, the memory map, text and copy routines will be present often. Don’t worry about what they do for the demo; just focus on the core content itself. Documentation of libtonc can be found in the libtonc folder (tonc/code/libtonc) and at Tonclib’s website.

Better copy and fill routines: memcpy16/32 and memset16/32

Now that I am using libtonc as a library for its text routines, I might as well use it for its copy and fill routines as well. Their names are memcpy16() and memcpy32() for copies and memset16() and memset32() for fill routines. The 16 and 32 denote their preferred datatypes: halfwords and words, respectively. Their arguments are similar to the conventional memcpy() and memset(), with the exception that the size is the number of items to be copied, rather than in bytes.

void memset16(void *dest, u16 hw, uint hwcount);

void memcpy16(void *dest, const void *src, uint hwcount);

void memset32(void *dest, u32 wd, uint wcount) IWRAM_CODE;

void memcpy32(void *dest, const void *src, uint wcount) IWRAM_CODE;

These routines are optimized assembly so they are fast. They are also safer than the dma routines, and the BIOS routine CpuFastSet(). Basically, I highly recommend them, and I will use them wherever I can.

Linker options: object files before libraries

In most cases, you can change the order of the options and files freely, but in the linker’s case it is important the object files of the projects are mentioned before the linked libraries. If not, the link will fail. Whether this is standard behaviour or if it is an oversight in the linker’s workings I cannot say, but be aware of potential problems here.

In conclusion

Tilemaps are essential for most types of GBA games. They are trickier to get to grips with than the bitmap modes or sprites because there are more steps to get exactly right. And, of course, you need to be sure the editor that gave you the map actually supplied the data you were expecting. Fool around with the demos a little: run them, change the code and see what happens. For example, you could try to add scrolling code to the brin_demo so you can see the whole map. Change screen blocks, change charblock, change the bitdepth, mess up intentionally so you can see what can go wrong, so you’ll be prepared for it when you try your own maps. Once you’re confident enough, only then start making your own. I know it’s the boring way, but you will benefit from it in the long run.